Is California’s farmland too dirty for legal cannabis?

California’s recreational pot market begins commercial licensing this January, and industry leaders have long-expected weed farms to go from clandestine to conventional.

That means abandoning the steep hills, poor soil and lack of water in the remote mountains of Humboldt and Mendocino Counties and instead farm traditional agricultural lands in the Central Valley. There, the ground is flat, the soil is rich, and water and labor supplies — as well as connections to city markets — are abundant.

However, rampant pesticide use across California’s farmlands, combined with the state’s de facto organic standards for legal cannabis could mean the best place for pot farmers is the wildlands where they started.

“We won’t be able to grow cannabis next to traditional, full-scale agriculture. It just won’t be practical,” said Hezekiah Allen, the Executive Director of the California Growers Association. “I live in Yolo County. I see the crop dusters. It’s not going to work.”

“This is going to lead to huge conflicts,” said Chris Van Hook, director of Clean Green Certified, a sustainable cannabis certification program that operates in place of the United States Department of Agriculture’s organic program. “We have had farmers who have had their entire year’s crop rejected because they were next to a blueberry field.”

It was likely broccoli in the case of Steve DeAngelo, 59, executive director of Harborside Farms. DeAngelo was one of the first large-scale pot farmers to set up in one of California’s most productive farmlands — the Salinas Valley.

In 2016, he set up 200,000 square-feet of cannabis greenhouses and grew weed following organic standards, but the farm’s first harvest failed testing due to pesticides — chemicals he said he never applied. He suspected contamination by pesticides blown over from crop-dusters on a neighboring broccoli farm.

This pesticide drift is rampant in modern agriculture. According to a 2016 review in the journal Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, up to 30 percent of pesticides sprayed on crops don’t end up where they’re supposed to.

“If you looked at a map of agriculture in the Central Valley, just the sheer concentration of industrial farming — you’d see the problem immediately,” said Dominic Corva, founder and social science research director at the Center for the Study of Cannabis and Social Policy, a Seattle-based nonprofit cannabis research organization.

Farmers in California’s Central Valley region, the state’s largest agricultural hot spot, applied to crops over 150 million total pounds of pesticides in 2015 (the most recent year pesticide data is available). That’s an average of 3,500 pounds per square milecomprising over 75 percent of all pesticides applied across the state, according to data from the California Department of Pesticide Regulation.

[Click here to look at an interactive map of where pesticides are applied in California]

Meanwhile, state pot regulators plan to set contamination fail levels in the ranges of a few parts per million. That’s because scientists generally don’t know the risks of inhaling burned pesticides, so the state has proposed some of the country’s tightest limits on over 60 popular cannabis pesticides.

“Unlike agricultural crops, when it comes to cannabis goods, scientists have rather limited knowledge of how much an average person may ingest or inhale or use a cannabis product on a daily basis,” said Charlotte Fadipe, assistant director of California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation, in an email.

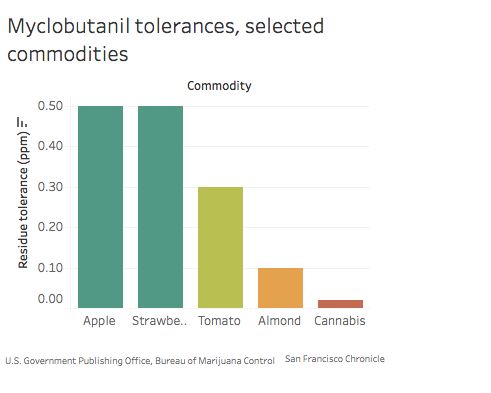

One pesticide threatens cannabis growers more often than any other. Farmers apply myclobutanil — often called Eagle 20 — to a variety of crops to prevent powdery mildew. Myclobutanil isn’t deemed harmful if eaten, but smoke myclobutanil and it turns into cyanide gas, which could be dangerous. Thus, regulators have proposed limiting myclobutanil on cannabis to levels that are as little as one five-hundredth of what’s allowed on other crops.

Pesticides drifting over from a conventional farm to a cannabis farm are only part of the problem. Exactly when farmers spray pesticides, as well as residual pesticides in soil and water are also major problems for pot growers eyeing regular farmland.

In the Central Valley, farmers spray pesticides on almonds and stone fruit just before the fall pot harvest, which is the “exact worst time for cannabis,” Allen said.

“This is a delicate flower,” said Swami Chaitanya, of Mendocino County’s Swami Select Cannabis. “If you’re going to spray Eagle 20 on this, you’re never going to get it off.”

And pesticides don’t break down easily in the environment. Some can persist in soils for up to 20 years, according to Reggie Gaudino, vice president for scientific operations and director of intellectual property at Steep Hill Labs, a cannabis testing facility based in Berkeley, Calif.

“The dirtier or more agriculturally inclined a place is, the more pesticides will get into the water,” he said. These hidden pesticides can be taken up by cannabis, a plant that is naturally good at pulling chemicals out of the environment.

At Harborside Farm, DeAngelo did two major things to prevent contamination. First, the farm began growing weed from seed, rather than risk buying cuttings, which are often dipped in pesticides. Second, Harborside installed massive ventilation systems to push filtered air through its greenhouses and keep pesticides from drifting in — much like how a wind tunnel keeps an indoor skydiver from hitting the ground.

It worked. After six months of transition time, Harborside Farms grew contaminant-free cannabis.

“It is not impossible for conventional agriculture and organic cannabis to co-exist,” said DeAngelo.“We’re doing it now. I just harvested 2,000 pounds of clean cannabis.”

But DeAngelo said his farm has resources smaller farms don’t, including full-time lawyers to talk to neighbors and county regulators.

Even with tight pesticide rules, there should be enough clean cannabis for all of California’s consumers — eventually. Californians use about 2.5 million pounds of cannabis annually, while the state produces an 11-million pound surplus for export.

“We have no problem producing clean cannabis in California. We just need to make sure it’s that cannabis that gets on the shelves,” Allen said. “At the end of the day, these are the best practices.”

Van Hook said cannabis’ current problems should yield new solutions for other crops.

“There will be agitation and conflict, but we’re moving toward cleaner practices,” he said. “Hopefully five to 10 years from now, it will lead to safer pesticides and safer application.”

Jackie Flynn is the Stanford Rebele Intern for the San Francisco Chronicle’s cannabis media startup, GreenState.